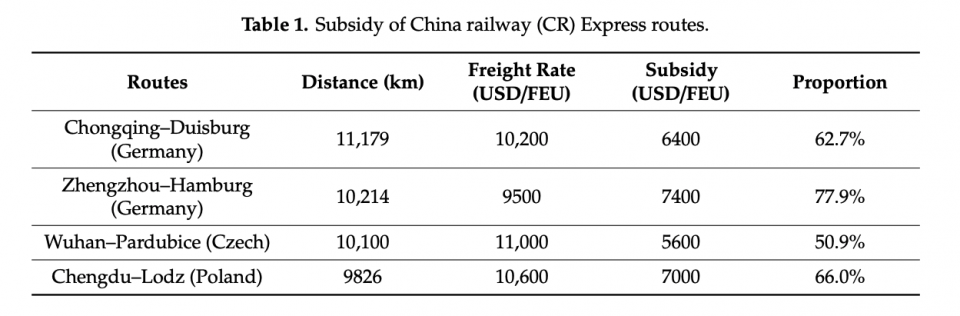

Financial subsidies divide into direct and indirect support. Direct support from local governments is paid out to operating companies. On the other hand, indirect are for the local railroad companies and help them reach a specific traffic volume to reduce tariffs. This in turn lowers the costs for the operating companies. Given that there is a continuous stream of government subsidies, the impact of the reduction on the operating companies could be significant.

How it all begun

The initial boom of China-Europe rail transport was a bubble created for political purposes. To get the top spot in the list of operating volumes, the local Chinese governments over-granted subsidies to help companies seize cargo sources. As a result, repeated routes entered the competition while low-value goods took over the market. Additionally, even empty trains needed to run punctually, to maintain the credibility of train companies and prove their ability to collect goods and preserve their rare sources. The cities where trains operate became solely competitive with each other, motivated by substantial government subsidies. Consequently, the «low price principle» instead of the «proximity principle» has become the market’s prevailing law.

Impact of subsidy reductions

The International Union of Railways (UIC) published a report in early 2020 regarding the China-Europe rail freight corridor’s potential. This report describes the possible impact of the reduction of financial subsidies on the operation of China-Europe trains. The withdrawal of subsidies will inevitably lead to a sharp decrease of volumes and their redistribution along existing freight routes. Unavoidably, the market will need time to adapt and cope with such a shift. The first to be affected will be the busy main transit route through Kazakhstan, which relies on subsidies for most of its cargo (except for select time-sensitive products such as fresh produce, machinery and biology). The northern route (through Manzhouli and Erlianhot ports) is likely to receive more market attention than the southern route (via Kazakhstan or the Trans-Caspian transport corridor).

Although the decline in financial subsidies will mean higher tariffs, i.e. possibly less competition than other modes of transport, China-Europe transportation will inevitably be subject to some changes to cope with this hurdle, reduce costs and maintain the best possible value for money quality. As a result, digitalisation and modernisation will undoubtedly be on the agenda, while cooperation and consultation between the various stakeholders will become increasingly widespread and intensive.

Game theory application

However, should government subsidies be removed altogether? A study conducted by Feng Fenling and others at Central South University, China, in late 2019 answers this question. The study uses Game Theory to model reasonable subsidies. In simple terms, the operation of the China-European liner is a game, and the level of government subsidies affects the interests of three players: the government, the liner and the cargo owners, who have their own goals and expectations in the game.

The government is the issuer of the subsidies and the rule setter. The subsidies’ original purpose is to ensure the China-Europe trains’ stability and regular operation and improve their competitiveness in the international transport market. For the liner companies, coordinating the cargo owners’ needs and the liner’s capacity, combined with these processes’ economic profits, are the primary objectives. This process takes place while reckoning all the possible economic profits. Moreover, the cargo owners have a relatively larger playground. Subsequently, they consider freight rates, timeliness, and service quality before deciding whether to use the Chinoeuropean liner.

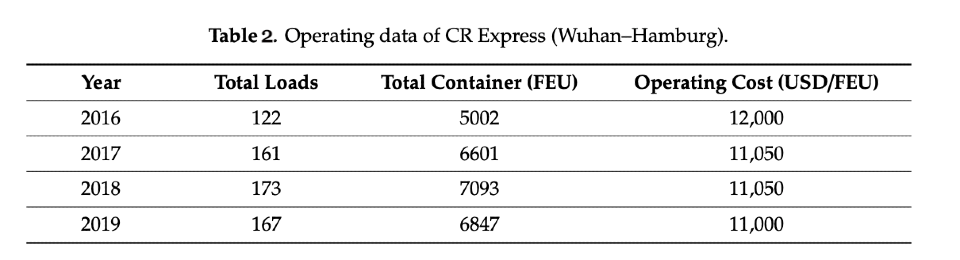

It is worth noting that the game in question here is not a jousting competition of life and death, but a cooperation bureau where the stakes and aim to a win-win cooperation to maximise all parties’ interests. On this basis, the scholars have modelled the Wuhan-Hamburg route as an example. The chart below shows the liner’s operation and the tariff change for this route between 2016 and 2019.

A reasonable subsidy model

The results of the study prove that government subsidies are necessary, but should not be too high. In the case of the Wuhan — Hamburg route, for example, the economic and social benefits of the train are optimal when the government subsidy between 2,000 and 2,500 US dollars per TEU. At the time of the study (end of 2019), the subsidy was between 6,000 and 7,000 U.S dollars per TEU, which is around 54 per cent to 63 per cent of freight rates. While this ideal amount of subsidy does not apply to every liner, gradually reducing the subsidy to around 20% could facilitate a win-win situation for all players.

Without considering other external market factors than subsidies, and with no cap applied on them; it is clear that there is no maximum amount of money earned by liner companies, as the higher the subsidy, the greater the benefit for them. Nevertheless, the model shows that social benefits no longer increase when the subsidy exceeds the threshold of 2,000 to 2,500 US dollars. In other words, when too high, a subsidy can stifle the incentive for liner companies to improve their service levels and thus reduce their attractiveness in the cargo market. It seems that subsidies are not so necessary. With less financial support, the economic and social benefits increase for liner companies since they improve their operations, and their reliance on support reduces. Thus, operating companies can better meet the timeliness and reliability expected by shippers on their own merits.

Not a battle

The study further points out that reducing China-Europe rail freight transport prices is not a panacea for its market share from maritime transport. The economic and social benefits maximise when prices balance between 10,000-12,000 US dollars per TEU (the exact amount is only for the Wuhan-Hamburg route). Once the tariff falls below 7,000 US dollars, the operating company will face losses, regardless of its operation level.

Suppose that the China-Europe trains’ tariffs need to retain at a certain level. In that case, their target cargo group is not cheap timber, but high-value products that are not price-sensitive, susceptible to time efficiency. This means that what is taking place between China-Europe and maritime transport should be an optimal allocation of cargo sources, not a battle for the market.