The European Union is China’s largest trading partner. China is the EU’s second largest trading partner after the United States, but it is catching up rapidly. The sustained growth of the Chinese economy and its integration into global supply chains have put China on a path to become the world’s largest trader and its largest economy, measured at market exchange rates. When measuring by purchasing power parity, it is already the world’s largest economy.

Since 2000, China’s real GDP has multiplied almost fivefold, while the EU’s grew by 20% and the United States’ by 41%. Over this period, Chinese growth has averaged 9%and has consistently stayed above 6%. At the beginning of the catch-up process, China had a very low level of development. Even today, per capita income in China amounts to only about one quarter of EU per-capita income at market exchange rates.

China’s exports have grown even faster than the rest of the economy, especially before the global financial crisis, though the rate of growth has slowed in recent years. China’s share of world export markets surged from 3% in 2000 to around 11%in 2015, and has since stabilised.

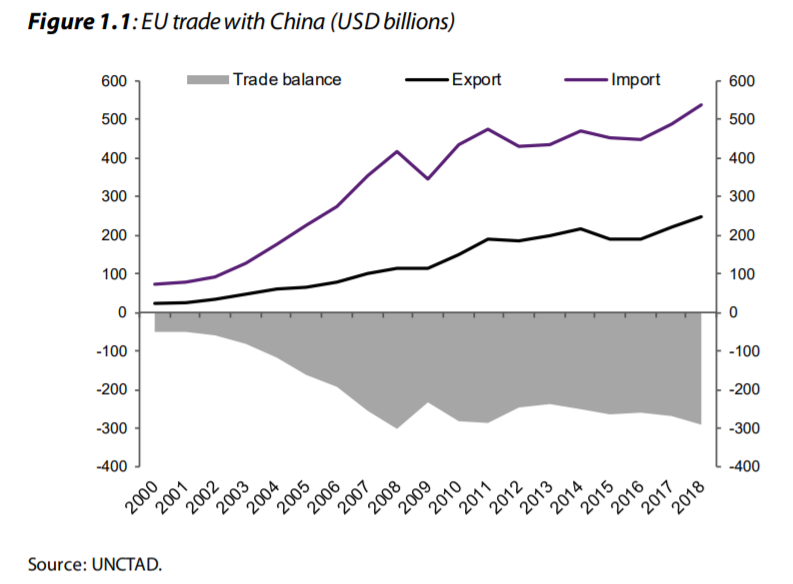

Since China joined the World Trade Organisation in December 2001, the EU’s goods exports to China have grown on average by more than 10% a year, and its services exports by more than 15% a year. This has generated ample benefits for EU producers and consumers. However, as imports from China have also grown rapidly, it has also caused some degree of disruption to EU labour and product markets.

Currently, China is the second largest market after the US for EU exports, but EU exports to China have been outpaced by China’s exports to the EU. The EU’s trade deficit with China has grown to USD220billion.

The EU’s trade deficit with China is significantly lower than the US trade deficit with China, but it is still important to note that the EU deficit with China is larger thanthat reported by Eurostat. Comtrade statistics which offer more accurate bilateral balance information between EU member states and China show that the bilateral balances between individual EU countries and China are lower than the Eurostat data suggest.

According to Comtrade, Germany runs a USD16billion trade deficit with China, while the Eurostat data show a surplus for Germany.

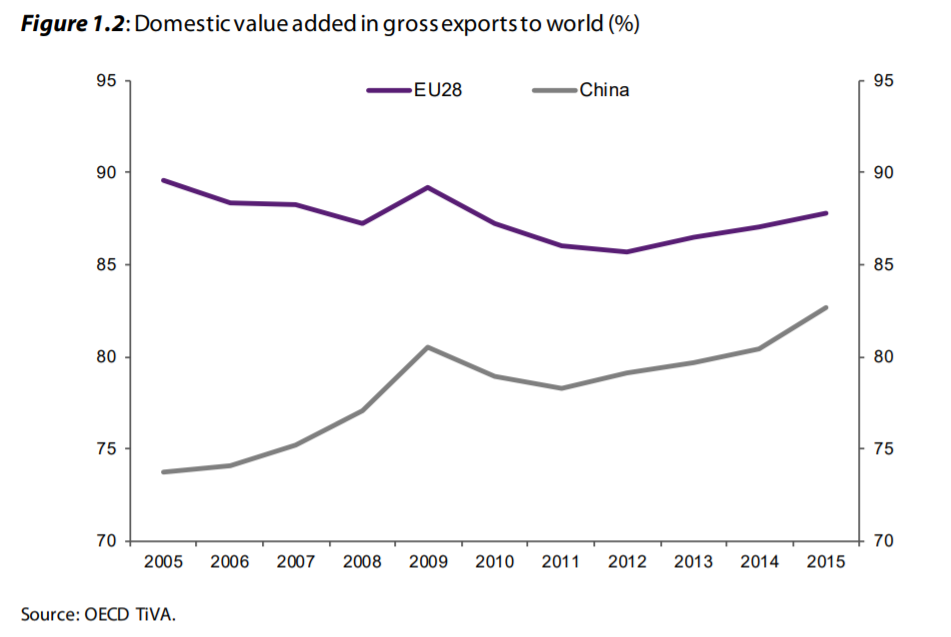

The difference in terms of value added between EU exports to China (relatively high) and Chinese exports to EU countries (relatively low) was so large that running a bilateral trade deficit in gross terms would overestimate the situation, compared to the actual trade deficit in value added terms. More recently, however, this has been less the case as China has moved up the ladder and the value-added component of exports has increased.

China has become much more important in the global supply chain. This has multiple implications for the EU-China trade relationship and the global economy more broadly. When it comes to the globaleconomy, the coronavirus outbreak is an important reminder of just how central China has become to global value chains. The shutdown of parts of China, especially Hubei province, has resulted in significant disturbances to global supply chains. The changing nature of China’s supply chains and China’s ascent of global value chains also affects EU member states’ integration with each other in terms of trade in intermediate goods. In fact, while the size of the intra-EU value chain has shrunk (countries are more loosely bound to each other in their exports of intermediate goods), EU member states have become increasingly linked to China for intermediate goods.

When China joined the WTO in December 2001, it benefitted from a reduction in the tariffs faced by its exporters, as other WTO members were required to adopt the most-favoured nation principle for China. Moreover, uncertainty about trade policy declined significantly. The WTO provides members with tools to protect themselves from unfair competition. In 2018, roughly half of the trade-defence instruments used by the EU were applied to China. In particular, anti-dumping measures were widely used and have been shown to effectively dampen trade. Their use increased significantly from the beginning of China’s WTO membership until 2006; since then the number of new cases has declined. In 2019, the EU initiated only two anti-dumping cases against China, out of a total of five anti-dumping cases initiated by the EU. China has initiated far fewer cases against the EU, with fewer than two new cases per year since WTO accession.