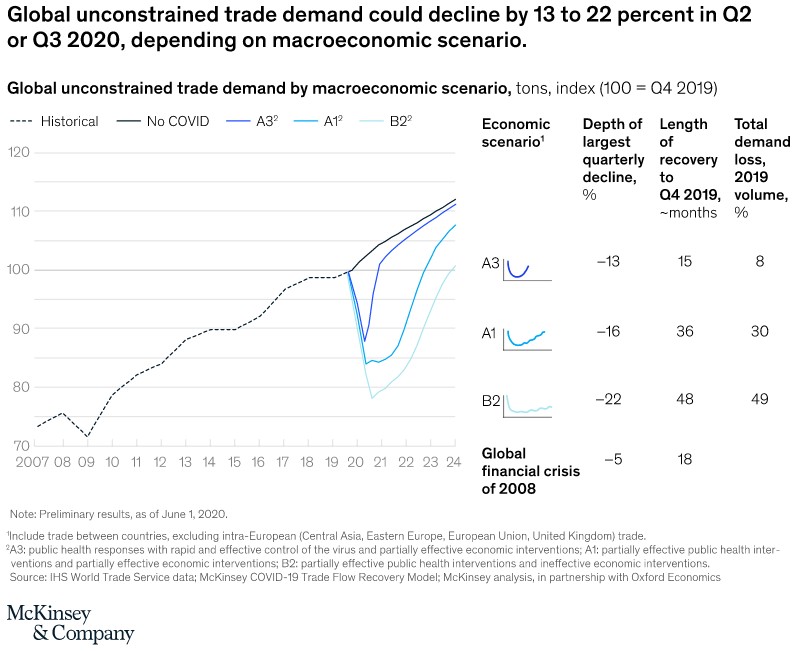

The recent research by McKinsey estimates that global unconstrained trade demand could drop by as much as 13 to 22 percent in the second and third quarters of 2020. By contrast, the largest quarterly decline in trade volumes during the global financial crisis of 2008 was around 5 percent. The estimates for global trade development are rooted in nine scenarios, developed by McKinsey in partnership with Oxford Economics, that model the different paths the global economy may follow, based on assumptions around the efficacy of both public-health and economic-policy responses as well as how businesses and households react to these initiatives. Detailed supply-and-demand modeling by commodity indicates that the effect on global trade will be substantially larger than on global GDP (which, for comparison, is estimated to decline by 3 to 8 percent in 2020) and considerably longer. In the scenarios modeled, trade volumes will take 15 to 48 months to recover to fourth-quarter 2019 levels, and the value lost will be equivalent to 8 to 49 percent of total 2019 trade volume. Trade and logistics companies are already feeling the consequences, with several road, air, and ocean transport companies reporting large dips in volumes versus the same period last year.

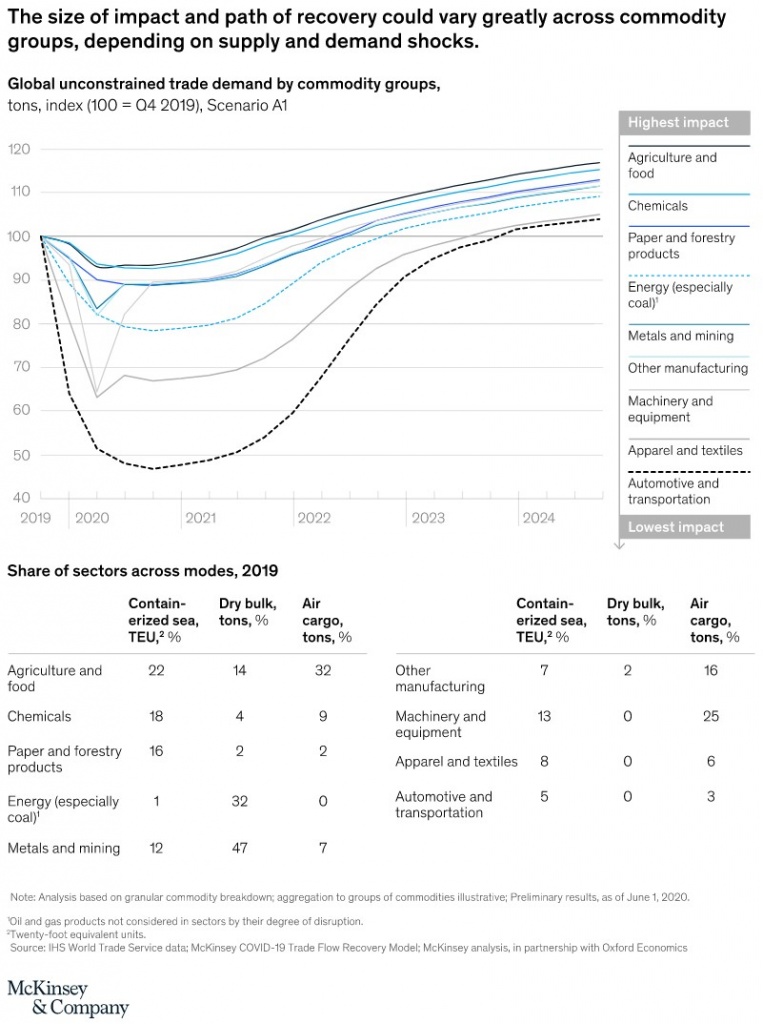

The impact of the crisis will vary significantly by commodity, with the shape and duration of the disruption determined by both supply shocks as economies undergo lockdowns and demand shocks due to the global economic downturn.

For instance, in an effective health response and partially effective economic-interventions scenario (scenario A1), the short-term trade volume of automobiles (expensive, durable goods) is expected to decline by more than 50 percent because of factory shutdowns and decreased discretionary spending by consumers. On the other hand, the trade volume of cereals (basic consumer staples) is likely to decline by no more than 5 percent. Supply will decrease only slightly because of the high degree of production automation and dispersed supplier landscape, and the increase in demand for at-home food consumption will make up for a fall in out-of-home consumption.

The degree to which each mode of transport and trade lane is affected depends on their particular commodity mix. When planning for the future, industry players should thus use insights from commodity-based modeling.

In scenario A1, for example, global unconstrained demand for air cargo will fall by 14 percent of pre-crisis volumes in the second quarter of 2020 and will not rebound to 2019 levels until around mid-2022.

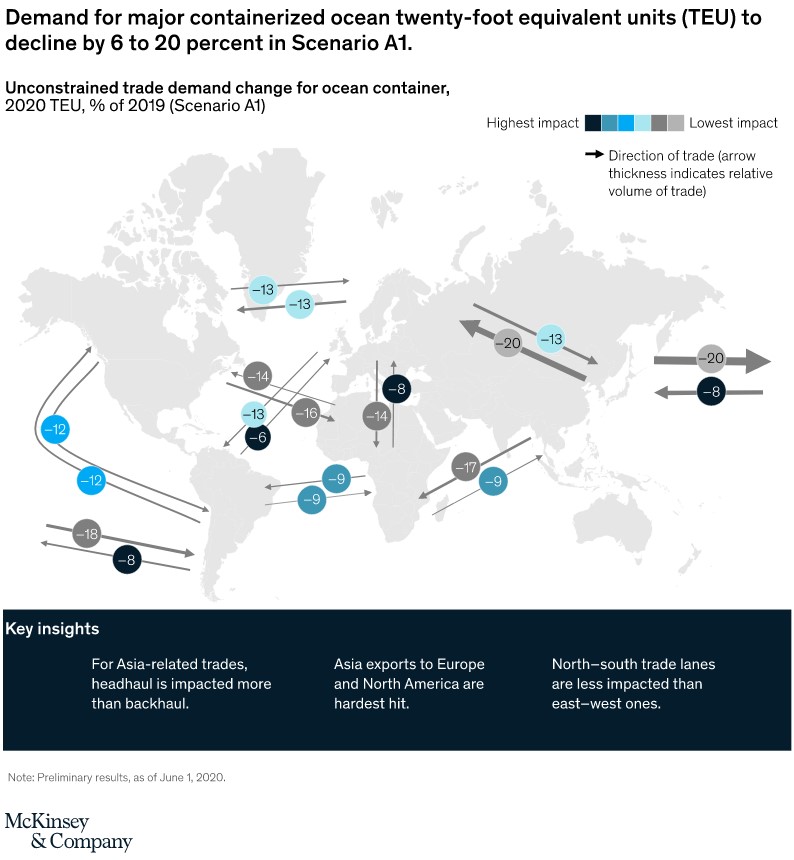

The demand drop for ocean transport will be about the same size, though the recovery may take slightly longer. Within ocean transport, the drop will be smaller for dry bulk than for containerized cargo, as dry bulk carries commodities that are less affected by the current crisis, such as agricultural goods. We expect dry bulk and containerized cargo tonnage to fall by 14 percent and 16 percent of pre-crisis volumes, respectively. Within containerized cargo, twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs) will take a larger hit than tonnage, falling by 19 percent of pre-crisis volumes; this will likely result in both a larger revenue impact and higher-than-average fuel cost as containers are heavier on average than before COVID-19.

The effect of the crisis on individual trade lanes will also vary significantly by country-specific COVID-19 development and by which commodities are transported on that trade lane. In containerized ocean trade, for example, the fall in demand in scenario A1 will vary from 6 percent on South American exports to Europe (which consist mostly of agricultural products) to 20 percent on some Asian exports (which predominately consist of machinery and equipment). If public-health responses allow for the rapid and effective control of the virus (scenario A3), then these declines may be limited to around 2 to 11 percent; they may be as high as 8 to 27 percent in the case of ineffective economic interventions (scenario B2). Across scenarios, the impact on Asian exports is likely to be larger than on Asian imports, and the impact on east—west trade lanes is likely to exceed that on north—south lanes. This variance may be founded both in the importing economies’ projected recovery—for example, China’s economy, and therefore its demand, is expected to recover faster than that of Europe and the United States—and in the commodity mix.

Now that most companies have managed many of the crisis’s immediate challenges, they need to think about their return to the next normal. Data on the impact of the crisis for each commodity and country—feeding up into impact per mode of transport and trade lane—would be a hugely beneficial input into three processes that are crucial in navigating a path through the crisis: