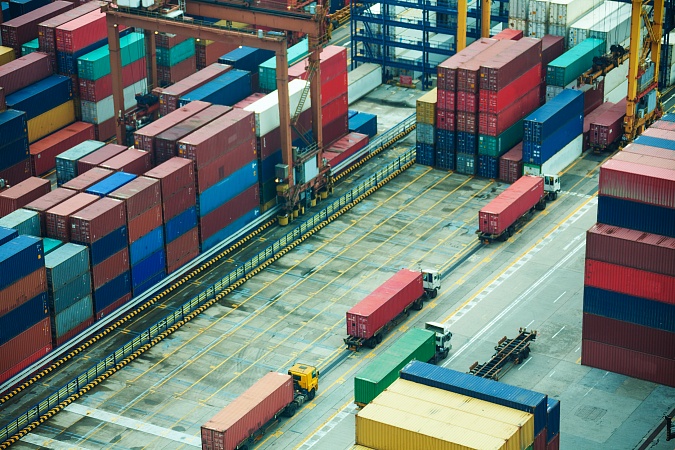

Cargo may face greater exposure to theft as containers accumulate at ports and terminals following the recent blockage in the Suez Canal.

This elevated risk of theft is among several secondary consequences highlighted by international freight transport and logistics insurer TT Club from the disruption stemming from last month’s blockage in the Suez Canal. But the insurance specialist regarded the greater vulnerability to cargo theft as the most significant risk issue, as operators seek alternative storage arrangements for containers or their contents.

In its advisory capacity as a mitigator of risk and loss in the supply chain, TT Club noted that although the Suez Canal was now functioning normally again, a reported 300 ships have been delayed awaiting transit, while many others were re-routed via the longer passage around South Africa’s Cape of Good Hope. It said global supply chains were already strained by the disruption caused by the pandemic and have been further challenged by the blockage of the Suez Canal, an artery that carries 30% of the world’s container cargo each year.

Mike Yarwood, TT’s managing director for loss prevention commented: «Beyond the delay to cargo on board those ships affected, there will inevitably be a knock-on impact for those involved in discharging the containers at destination ports when they finally arrive, as well as the final mile delivery carriers. While the immediate impact may be a lack of cargo arriving when expected, presenting market supply challenges, it is when the cargo does start to turn-up that further potential risks emerge.»

TT Club highlighted that the arrival of large volumes of laden containers, coupled with the requirements for hinterland distribution, will create disruption at ports and terminals, «straining throughput and yard capacities, and creating accumulation of cargo. This is a complex risk and one that will not only affect destination hubs».

The situation will also aggravate an already widely reported imbalance of container equipment especially on the East to West trade routes as laden containers are tied up and consequently empty availability to reposition to shipment areas worsens.

Yarwood further stressed: «The risk of theft at ports and freight depots in this scenario is heightened and a greater focus on security is required. Whether it simply be at an overspill holding or storage area, or temporary warehousing, wherever and whenever cargo is not moving, it is more likely to be stolen.

«Those active in the supply chain should be mindful of these security risks. Due diligence undertaken to ensure that any third-party provider of storage is adequately resourced to meet these demands, is a prudent step to take in these circumstances.»

Yarwood said security was «clearly the most dominant of the risk issues as operators seek alternative storage», adding: «Whether it’s taking up buildings not usually used for storage or laden vehicles parked adjacent to a full warehouse, or simply facilities unfamiliar to the operator, the security regime may not be of a similar standard. This concern is not just limited to fencing, lighting, security patrols and CCTV, but also communication with hauliers delivering cargo to the unfamiliar premises. There is also the constant danger of vehicles being diverted into the hands of criminals; so-called round the corner theft.»

Highlighting other risks, TT Club noted that particularly in Europe, driver shortages «are already expected to soar through 2021, as highlighted by a recent International Road Transport Union (IRU) survey. This will exacerbate the difficulties in delivering import cargoes and picking-up consignments for export.»

The freight risk specialist said the overall lack of capacity to move containers «has the potential to create additional challenges. Those seeking to secure road haulage capacity should be mindful of the associated security risks outlined in the recent TT Club/BSI joint cargo theft report, and take the advised steps in mitigating the threat of theft.»

Yarwood concluded: «The last decade has witnessed many in the supply chain drive towards streamlining and operational efficiencies. Such measures have included reducing the number of suppliers and introducing ‘just in time’ principles to lessen the burden of unnecessary inventory costs.

«Experiences over the last twelve months through the pandemic, the Brexit transition and more recently the Suez Canal blockage, bring into question this bias towards efficiency and cost reduction. If such are achieved at the expense of resilience, is this policy the correct one? The new normal might see many stakeholders increase their focus on contingencies and adopt more a ‘just in case’ philosophy than a ‘just in time’ one.»

That conclusion is consistent with others since the start of the pandemic, and even since the recent Suez blockage, which have indicated a growing intention among supply chain professionals to increase resilience and reduce risks of supply disruption — for example, by increasing numbers of suppliers and their geographic spread.