Edgerton complains that we are too obsessed with innovation — the «new» — when in fact the great majority of significant breakthroughs have been clever tweaks of the old, generating wealth and enhancing productivity over the past half-century. Much-lauded new inventions may be significant, but they may be neither useful nor pervasive for generations, if ever.

Meanwhile, it is the useful but very old inventions that continue to stimulate most of the improvements in our lives. Think of trams, that still today unglamorously move millions across Hong Kong Island every month. Think of electric cars , which first burst onto the market in Des Moines, Iowa, back in 1890. Remember that the first mention of the «fourth industrial revolution» was back in the 1940s.

Edgerton suggests that a characteristic feature of our age has been imitation, not innovation. And nowhere is this better illustrated than by China’s «reinvention» of rail.

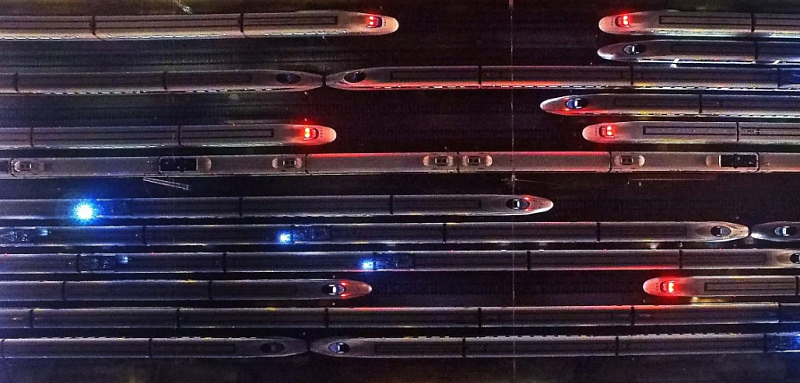

Since the opening of the Beijing-Tianjin high-speed link in 2008, China Railways has built 141,000km of new railway lines, 36,000km of them high-speed lines that can whisk travellers around at 250km an hour. The aim is to add a further 60,000km of railway lines by 2035 — almost half of these high-speed lines. The 2035 plan says every city over 200,000 people should by then be linked up to the country’s rail network, and every city over 500,000 served by high-speed trains.

High-speed trains are not new. Japan launched its Shinkansen in 1964, and France its TGV two years later. The difference is that Japan today boasts just 3,041km of high-speed rail line, and France just 1,900km. They beat China to the concept of high-speed rail by decades, but China has massively extended the utility of the technology.

Nor are trains carrying cargo a new phenomenon. Trains have trundled bulk cargoes like grain, cement and timber across the United States for a century. But what is happening in China today feels radical, not just within China, but also across China’s «belt and road» network,

spanning Central Asia and north into Europe or south across Africa.

The high-speed cargo rail network is growing rapidly for a range of reasons. It helps that China Railways is spending over US$114 billion a year on new railway lines and rolling stock. China’s unglamorous engineers take their infrastructure uniquely seriously — not just roads, railways, ports and power plants, but also wind, solar and hydrogen power and 5G telecommunications

The movement inland of thousands of China’s manufacturers (and foreign investors), escaping the high costs of the coastal provinces and shifting to serve an increasingly important domestic consumer market rather than exports, has raised the need for high-speed delivery of components along fast-growing internal supply chains.

The development of e-commerce across the country has created huge demand for high-value e-delivery services, with rail carriages proving highly competitive both on speed and cost against both road hauliers and air cargo carriers. The railways’ lower environmental footprint also makes rail freight eco-fashionable.

But where rail development really becomes interesting is when you look at the land mass separating China from Europe — Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan. From the first novel rail-freight services in 2011 linking Chongqing to Germany, China Railways is now supporting 1,200 trains a month linking 43 Chinese cities with over 40 cities across Europe.

A propaganda coup in June was to deliver a trainload of personal protective equipment and other medical supplies from Yiwu on China’s east coast to Madrid along what is now glibly being called the «health Silk Road».

The 1,200 trains in July carried a total of 113,000 containers into Europe, a 73 per cent increase year on year. Under the belt and road concept, this China-Europe spine aims not just to enable goods to travel between these two huge consumer regions, but to develop manufacturing «nodes» in Central Asia and to draw in the growing markets of Southeast Asia and even Africa.

At least 28 railway projects are currently being developed under China’s Belt and Road Initiative, with three massive rail investments on the China-Europe «spine», six reaching down into Laos, Thailand, Myanmar, Malaysia and Indonesia, and a further eight spanning Africa.

Before we get too carried away, it is important to remember that 1,200 trains carrying 113,000 containers would fill just six of the most modern container ships that depart daily from Shanghai or Hong Kong, and compares with over 36 million containers carried annually around the world.

China Railway has this year been accounting for 2.5-2.8 per cent of the China-Europe freight, and aims to build on this to create a robust and sustainable niche — slower than air cargo, but costing barely 30 per cent per kilo; more expensive than sea cargo, but getting to Europe in 12-17 days compared with around 35 days by sea.

There are also substantial challenges to be overcome. The most significant is that rail tracks across Russia, Kazakhstan and other former Soviet states are 89mm wider than those in China and Europe, which means that containers have to transfer trains twice on the journey to Europe’s main hub in Duisberg, with possibly days lost as containers are queued to change at the Kazakhstan or Poland border.

The second main challenge is the huge investment cost. Few countries have China’s deep pockets or its long-term planning vision, but even by China’s standards, China Railways’ estimated 5.28 trillion yuan (US$770 billion) debt is eye-watering.

As the World Bank notes on the release of a recent report on China’s rail development: «China’s high speed rail development sits somewhere between a shining example of infrastructure planning, and a cautionary tale of unsustainable government subsidy.»

Professor Edgerton would relish the way China’s engineers are reshaping trade and logistics with their railways, and illustrating so vividly the power of the old to shock.

David Dodwell researches and writes about global, regional and Hong Kong challenges from a Hong Kong point of view.